“Most people seem to be interested in turning their dreams into reality. Then there are those who turn reality into dreams. I belong to the latter group.” ~ Allen Say

Open any one of Allen Say’s picture books, and chances are good you will see lots of windows and doors.

Some of these are the wood and paper shoji doors found in Japan, while others are flat panel doors or double-hung windows commonly found in homes across America.

For Say, these may be portals to a dream state, concrete symbols of conflict and exclusion, or simply the way an outsider views the world — looking at the lighted windows in a cozy home and wishing he belonged inside, or sitting inside viewing the rest of the world through panes of glass.

I’ve been a big Allen Say fan since the late 80’s, traveling back and forth between Japan and America with him via his books, keenly identifying with his dilemma of a dual identity, walking the tightrope between cultures.

They say we spend the first half of our lives getting through childhood, the second half, trying to come to terms with it. Many of us who write for children admit we write stories to try to understand ourselves better, or to create the happy endings we missed.

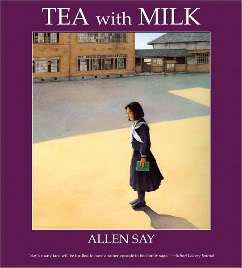

Both of these titles feature Say’s mother, a Japanese American born in Oakland, California. Like her son, she was unhappy when forced to live in another country.

This seems to be especially true of Allen Say, whose work revolves around such themes as alienation, displacement, cross-cultural assimilation, and the search for identity. He was born in Yokohama, and his childhood was largely unhappy — it was war time, his parents divorced, and he didn’t get along with his father (a Korean orphan raised in Shanghai who wanted Say to become a businessman, not an artist).

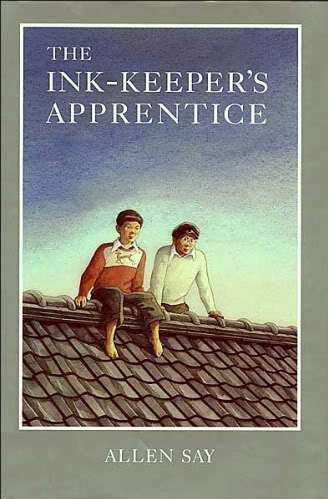

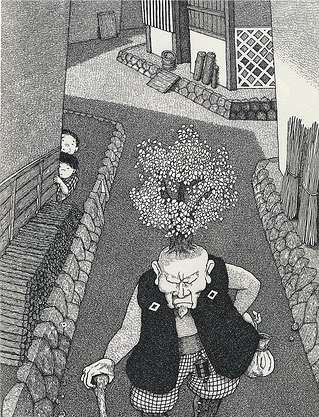

When sent to live with his grandmother at age 12 to attend middle school in Tokyo, the situation became so unbearable, Say eventually moved into his own apartment and apprenticed himself to cartoonist, Noro Shinpei. A pretty extraordinary set of circumstances, even by today’s standards — but from an early age, Say was determined to make a home wherever he could and live on his own terms despite the disruptions that befell him.

In Shinpei, Say found not only a master to nurture his budding artistic talent, but the father figure he so desperately needed. Say calls his four years with Shinpei (which are chronicled in his novel, The Ink-Keeper’s Apprentice), as among the happiest of his life. The apprenticeship ended when Say’s father decided to move to America, and Say went with him. Unfortunately, the “big adventure” Say was expecting translated into an all-white military academy, where he was separated from everyone else, living in a modified storage room. He was expelled for smoking cigarettes in his room, but was encouraged to pursue his art after enrolling in a public high school.

He took weekend art classes, and after graduation, moved back to Japan. Disillusioned by how much it had changed, he returned to California, and worked briefly as a sign painter’s apprentice. He married and enrolled at UC Berkeley to study architecture, but shortly thereafter, was drafted and sent to Germany. His first photographs were published by the Stars and Stripes.

After returning to the States, he worked as a commercial photographer for about 20 years, during which time he also did some illustrating. One of these early books, How My Parents Learned to Eat, by Ina R. Friedman (1984), introduced me to Say’s work, and was the first “multicultural children’s book” to inspire my own writing.

I didn’t learn until recently that Say actually didn’t like the way the book turned out because of its poor color reproduction. He had vowed never to illustrate another children’s book ever again. But Houghton Mifflin editor, Walter Lorraine, convinced Say to illustrate Dianne Snyder’s Boy of the Three-Year Nap, a retelling of a Japanese folktale, which went on to win a Caldecott Honor and Boston-Globe Horn Book Award in 1988. This marked a turning point in Say’s career, since he quit commercial photography and has devoted himself to creating children’s books ever since. He won the coveted Caldecott Medal for Grandfather’s Journey in 1994.

What especially fascinates me about Allen Say, is that he is the only illustrator I know of who paints the pictures first and writes the words afterwards. Although most of his books deal with deep issues, he never starts out with any sort of “message” he wishes to convey — he starts sketching to discover what ideas are floating in his subconscious:

First I doodle. Then I make pencil drawings. When I feel good about what’s coming out, I put that on a stretch watercolor paper and start painting. When all the paintings are finished, I put words to them. My editor thinks the way I work is very unnatural — I wouldn’t get a good grade in school — but it’s the best method for me.

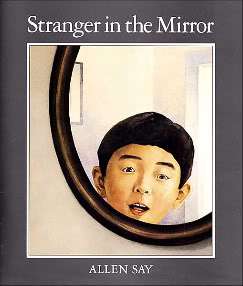

Say also admits he doesn’t enjoy writing, calling it “the most unnatural thing I know of. No amount of words can paint what something really is.” Not too surprising for someone who didn’t speak a word of English until he came to America at age 16. Freely admitting that he aims to please only himself with his books, he has also tackled themes like aging (Stranger in the Mirror), the source of creative inspiration (Emma’s Rug), and difficult topics like the Japanese internment (Home of the Brave), in stories that seem to speak more to adults than children.

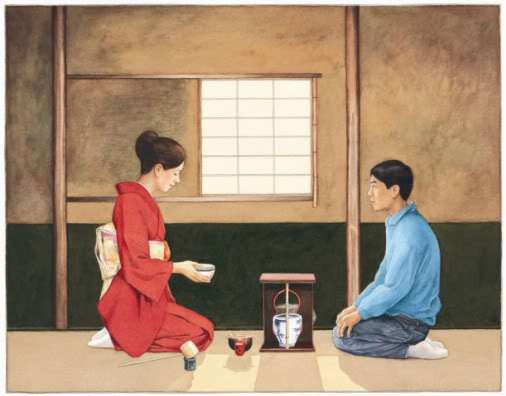

Critics speak of his “masterful watercolors,” often using words like exquisite, elegant, translucent, and evocative, when describing Say’s understated, largely tranquil style. The lines are clean, the spaces uncluttered; there might be a feeling of calmness, but the subtext is poignant, intimate, far-reaching.

Many of his illustrations resemble formal portraits, showing great care with lighting. No doubt his many years as a photographer has enabled him to capture an emotion as it occurs in a split second on canvas. That’s where the stories lie — in those facial expressions, the pain or bewilderment behind the eyes, allowing us, as outside observers, to enter the lives of his characters as we turn the pages. Beautiful restraint.

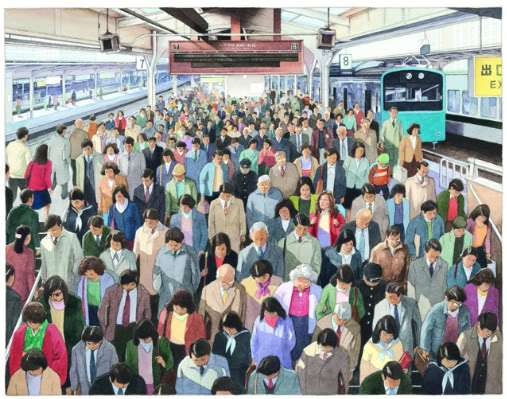

Say’s latest picture book, Erika-San, released in January 2009, once again has a cross-cultural theme. A young American girl sees a print of a small Japanese cottage with lighted windows hanging in her grandmother’s home, and becomes fascinated with Japanese language and culture. She studies all things Japanese throughout high school and college, eventually landing a teaching job in Tokyo, but when she finally gets there, she is dismayed by how big and crowded it is — not at all like the ideal vision of Japan she’s had in her mind all along.

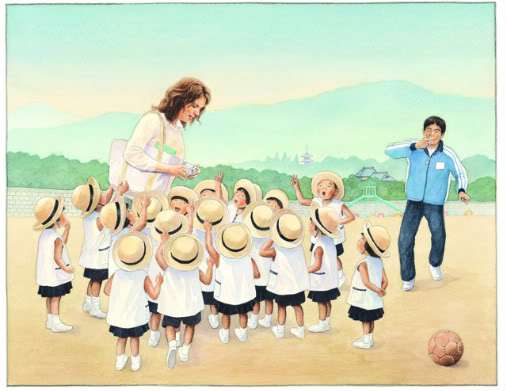

Fortunately, she’s able to transfer to a more rural, remote location, and meets another teacher, Aki, whom she eventually marries. The final spread of the book shows a small farmhouse, “nested in the green hillsides of old Japan. And there Erika-san stayed, home at last.”

Again, lighted windows, but the main character is happy inside — a direct contrast to the darkened windows of the internment camp buildings in Home of the Brave, where a group of children wearing name tags begs the main character to take them home.

Say likes happy endings; couples marry, children with problems have both parents to help them through (they often look in on their children from open doorways), and when things go dark, he will paint in the light. In his 1994 Caldecott acceptance speech, he said, “life’s journey is an endless dreaming of the places we have left behind and the places we have yet to reach.”

♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥ ♥

Read the full text of Say’s 1994 Caldecott speech here, where he mentions the astonishing discovery that Lois Lowry, who won the Newbery the same year for The Giver, attended the very same middle school in Tokyo while Say lived there, and that now they even share the same editor.

Visit the Official Publisher’s site for Allen Say here.

You must read Yuriko Say’s essay, “My Father.” It was written when she was 13, and is so telling!

And check out this great interview at Paper Tigers.

*Spreads from Erika-San posted by permission, copyright © 2009 Allen Say, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

He’s right: you can’t paint what a thing really IS with words, but I keep trying. It’s the grasping and dreaming and running after that gets me. But if I could PAINT like him, I’d throw my laptop away!

LikeLike

Tanita Says 🙂

His daughter’s portrait of him makes me want to hug him. He worried that he couldn’t write and express the way he wanted to, but I wonder if I wouldn’t trade my words for his paint. His art is so evocative and expressive. Wow. Thanks for sharing this.

LikeLike

There are frustrating limitations no matter what art form we chose. I keep trying to make words the equivalent of music. Yeah, that also results in grasping and dreaming and running after.

LikeLike

Re: Tanita Says 🙂

Thanks for reading, Tanita. I know what you mean about wanting to hug him. I imagine he would give us both demerits!

LikeLike

Jama… BEST. POST. EVER.

I am so moved. Thanks to this post I now know so much more about Allen Say… and about you. :o) And now I have more books to search for and read!

I remember reading How My Parents Learned to Eat in the third grade. I loved it so. I still do. And now I wonder, was it because it was the VERY FIRST story with an Asian character that I ever read? For some reason, up till the third grade all the characters in all the stories I read were either white, black, or Mexican….

Tarie

Into the Wardrobe

LikeLike

Thanks, Tarie. I had to wait until I was an adult to read How My Parents Learned to Eat, but it had the same effect on me. Just seeing chopsticks in a book made me so excited!! Though I had read folktales like the Five Chinese Brothers and the Story of Ping when I was a child, Friedman’s book was the first with a contemporary setting. An eye opener, to be sure.

LikeLike

Wow. What a great feature. Thank you.

That is fascinating that he paints the pictures first.

I’m a big fan, too.

Jules

7-Imp

LikeLike

Yeah, I found his process very fascinating, and can even identify, to some extent, with the “unnaturalness” of writing.

LikeLike