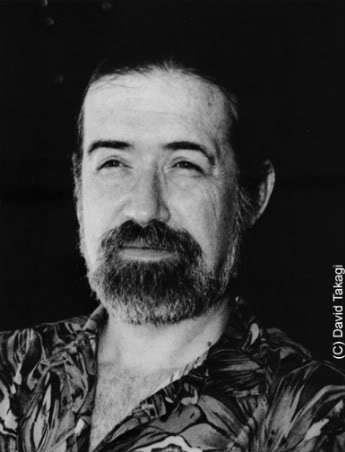

Today I have the distinct honor and privilege of welcoming award winning children’s author/illustrator, James Rumford, to alphabet soup! As I mentioned in the profile I posted recently, Jim has published over a dozen picture books; most are works of historical fiction or biography, which display his passion for and unsurpassed knowledge of ancient languages, alphabets and numbers.

A native of Long Beach, California, Jim is a world traveler who has lived in Manoa, on the island of O’ahu, for the last thirty years or so. There he creates gorgeous picture books that are a distinctive blend of art, calligraphy, lyrical text, and innovative book design. Jim also makes beautiful handmade books for his own company, Manoa Press.

In 2008, Jim published Silent Music (Roaring Brook Press), and Chee-lin: A Giraffe’s Journey (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). I asked him about these two projects, his love for languages, and all about his general creative process. You will see, by his answers, why he has been called a Renaissance Man.

Aloha, e Jim. Komo Mai!

By all accounts, you’ve lived a full, fascinating, adventurous life, with first-hand knowledge of many cultures. How did you come to write and illustrate children’s books?

I want to start by saying that I love language as well as I love art, and I find the children’s picture book the perfect medium to combine both loves. Picture books make it possible to explore the interactions between language and art. To put it simply: the fact that a picture is worth a thousand words is as true as the fact that a word is worth a thousand pictures.

This yin-yang, ever moving aspect has always intrigued me. When I was a boy, I had wanted to become an artist when I grew up. I would paint alongside my father, from whom I learned to draw and paint. As the years went by, I became more and more dissatisfied with painting pictures and hanging them on the wall. For me, there was more to drawing and painting than that. It wasn’t until I was in my forties that I realized what I really enjoyed: drawing pictures and attaching words to them.

My wife, Carol, is always trying to get me to paint pictures for the walls in our house. I am not interested. People want me to paint them pictures as well. I am not interested. I tell them to go buy my books if they want one of my pictures. To sum up what I have said: a picture for me is not complete unless it is accompanied by words.

Your passion for ancient languages, alphabets, and numbers has inspired and informed most of your picture books. I read somewhere that you speak more than a dozen languages. Please list some of these for us, and explain what first sparked your interest in linguistics. What’s your favorite language to speak or write?

Words have always been important to me. Not just words in English, my native language, but words in any language. I have learned a dozen or so languages: French, German, Portuguese, Latin, Persian, Chinese, Kinyarwanda, Hawaiian, etc. I never tire adding to my linguistic repertoire. By this I don’t just mean adding another language to the ones I already know. Rather, I mean that by learning another language, I enlarge my English horizons as well. I discover, by learning a foreign language, ways to express myself in English in new and different ways.

One example that comes to mind is “the fragrance of books.” This is a Chinese expression to describe someone who is scholarly, learned. I once wrote this sentence about Famous Amos’ cookie store and his promotion of literacy: His store has the smell of cookies and the fragrance of books. My editor made me change the sentence to the “fragrance of cookies” and the “smell of books.” She was right “English-wise,” but I was disappointed.

My love of language must be rooted in my genes — somewhere deep inside. When I was eight, my mother couldn’t get me to go to bed until I had copied all of the Chinese characters out of a children’s classic, You Can Write Chinese, by Kurt Wiese. I found Chinese fascinating. Still do. In fact, not only do I love the sounds of a foreign language and the expressions that one can find in each, but I also love foreign languages that use different writing systems. I have learned Chinese and Persian, some ancient Egyptian, and Greek.

The stranger the writing system is to my eyes the more I am intrigued. One system, the Cherokee one, which I wrote about in Sequoyah, is a good example. It looks like Roman letters but it is not. What is more, the letters that do look like Roman ones don’t have the same values. For example, the letter “A” is pronounced “go!”

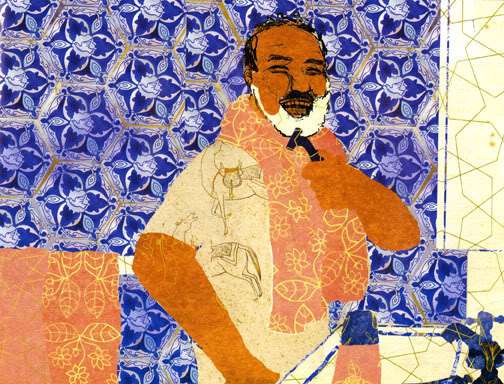

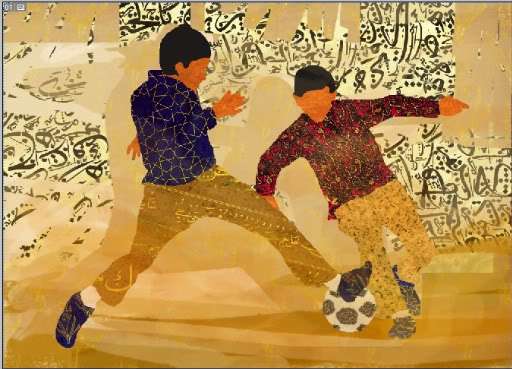

Congratulations on the publication in 2008 of two brilliant, exquisitely crafted books: Silent Music and Chee-lin: A Giraffe’s Journey. Silent Music, aside from being a very touching story about young Ali, coping with the bombings of Baghdad in 2003, is a beautiful tribute to the art of calligraphy. How did you learn Arabic calligraphy, and do you find it more difficult than Chinese calligraphy, because of its continuous form?

I like writing systems because I love their beauty. Two of the most beautiful in the world? Chinese and Arabic. Chinese I learned by practice throughout the years. The apprenticeship is never ending. The practice is constant because the forms of the characters can become so expressive of mood and inner strength.

Arabic is different. It is a more rigorous system in that the shapes are already defined. The trick with Arabic calligraphy is the same as it is in English calligraphy: learning to reproduce time-honored shapes and to be able to write them flawlessly time after time.

I learned the Arabic alphabet from a Persian friend in high school. I went on to Berkeley, studying Persian, but it wasn’t until I went to Afghanistan as a Peace Corps volunteer that I had formal training in Arabic/Persian calligraphy. I loved having an elderly gentleman scholar come to my house in the dead of winter and him teaching me the correct strokes.

Writing another language, learning the calligraphy, is another way of widening my world view. The deeper I go exploring and the more I learn, the more I am able to express myself in new and different ways. This idea of widening one’s horizons is the theme of my Calabash Cat — a strange book, I might add. Strange? Yes, because every time I read it, I understand it in a new and different way.

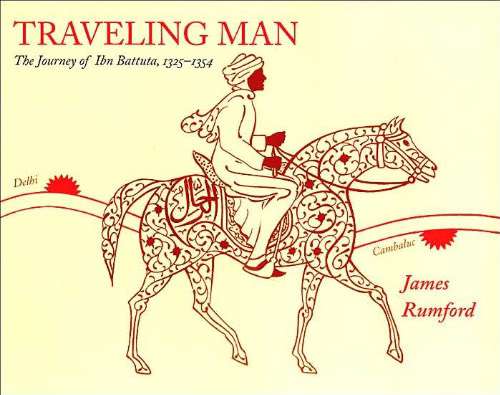

You’ve said that with Chee-lin, where the text is divided into short chapters, you wanted to “bring out the words,” and that you were trying to create a new kind of genre. Though similar in format to Traveling Man, the narrative in Chee-lin is decidedly longer. Can you tell us more about your desire to experiment with picture chapter books?

Chee-lin began when I read Gavin Menzies’ 1421: The Year China Discovered America. In that book, among the unsubstantiated things (to my mind) was the story about the giraffe. I thought that this story would make a good children’s book, but as the book evolved I knew that it could not be a typical children’s picture book. I decided to experiment with adding chapters to a picture book. I had tried this out to some extent with Traveling Man, but this time I wanted to go further than I had gone before. This is not a new idea. One of my favorite children’s authors, Holling C. Holling, used this technique extensively.

One of the reasons was that I thought that the subject matter and my story were not for young picture book-age children. Rather, it was a book for older kids who might be into “chapter books.” In retrospect, I wish that I had made the book smaller in format so that it looked more like a chapter book.

Picture books are usually eschewed by older kids. They think of them as “baby books.” This is too bad, because a lot of picture books aren’t for the audience the publishers intend them for.

For Chee-lin, I wanted to do paintings to illustrate the story. The paintings are a bit old-fashioned in that they illustrate only part of the long text on the facing page. I toyed around with the idea of titling each picture (in an old-fashioned way), but found that would add confusion, not clarity.

Writing Chee-lin was fun because it was way longer than my other books. I had a number of characters to “develop” and I definitely wanted to set the scene in the different stages of Tweega’s life. Of course, I didn’t let the words do all of the work. I used the pictures and the designs surrounding the text to help transport the reader to far-away places and long-ago times.

I wrote most of Chee-lin in one sitting. The words just started flowing and I typed as fast as I could. Unfortunately, when I got to the end, the telephone rang and I stupidly answered it. When I returned to my computer, I couldn’t remember the ending. The flow of words stopped. It took me a year to think of an ending, which only came after I read Bambi and saw how Felix Salten brought his story to an end.

Could you briefly describe your overall creative process, once you’ve hit upon an idea? What role does the computer play in creating your pictures, and how do you think it has influenced you as an artist?

When I begin a book, I start with the words. They are that important to me. When I have the words just the way I want them, I begin drawing. This doesn’t mean that I haven’t been seeing pictures in my head, or I haven’t been shaping the book (layout-wise) in my head. It means that when I am finished with the verbal aspect of the book, I begin with the visual aspect. Over the years, I have noticed something odd about this: once I have finished the words and have begun the pictures, I find it hard to switch back to working on the words. It’s as though there’s a toggle switch in my brain that shuts off the words once the art starts flowing.

I find that the art is the harder of the two “forces” to control. It might be that in drawing, there is more invested in any one picture than there is in any one story. By this, I mean that it is easy to change words, whole paragraphs. It is another matter to redo an entire picture. Worse, eliminate pictures that may have taken weeks to do.

Fortunately, today with the computer, it is becoming easier and easier to make changes on a picture. Now, I scan my sketches onto the computer, use Photoshop to correct them, print them out on art paper, and finish them up by hand. This relieves a lot of the stress of doing the art because if the picture doesn’t turn out, it is just as easy to print out another and begin again.

Even easier is to do the art in the computer. This was the case with the art in Silent Music. That art began with sketches and I finished it up in the computer. For a book that is to appear this year, called, Tiger and Turtle, the art doesn’t exist except in the computer; there are no sketches because I used the mouse to draw all the scenes.

I love working with the computer because it allows me to experiment with color, form, shape, medium. It frees up my mind to come up with things that I don’t think would be possible otherwise. This is equally true with writing the words and how they are laid out on the page.

Page design and book design are another aspect of children’s books that I really enjoy. For me, a children’s book is a movie, and designing the book is a way of creating a little theater with actors and scenes and dialog. For all of my books, I have had a major hand in designing the pages and the book as a whole. Silent Music is certainly an example of this, as the words, the illustrations and the layout of the book are so interconnected for me that it would have been impossible to give the text and the illustrations over to someone else to “assemble.”

Please describe your studio/workspace, and take us through a typical day.

When I write, I sit at my computer, which will soon be moved down to my renovated studio (it looks out on the yard and the hill, and above me, on the ceiling, I have put a Persian poem by Hafiz — again, words and art working together). I get up early, at five, and begin.

Writing a children’s book is not like writing a novel. Ninety percent is inspiration, the same kind of inspiration that is involved in writing a piece of poetry. Another 90% (I know that is illogical, but how else to describe the next step) is polishing the words. As soon as I have the words I want, I begin by placing them on pages. If the page breaks seem logical, if they add to the rhythm and the tension in the book, I move on to the next stage, sketching the illustrations.

When I do art I work at the kitchen table. This is to change as well. I will work in my studio, but I have a feeling that I will still sit at the kitchen table and draw. The kitchen is a nice place to work.

My personal favorite of all your books is Sequoya, which is dedicated to your father, Sydney, “who would stop the car to read every historic marker and who would certainly have told us this story.” What was your childhood like? What books, authors, or artists influenced you the most?

I didn’t read a lot of books when I was a child. I don’t read many today. I am, of course, talking about fictional work. I read tons of nonfiction. I am very careful what fiction I put into my brain. It has to be good. It has to be well written. I don’t read for plot. I can think up a million plots. I read to enjoy the way the author expressed him/herself.

When I was little, one of my favorite books was Hoot Owl, by Mabel LaRue. It was about a white pilgrim boy who got lost in the woods and was brought up by Indians. He learned their language and their customs. I was fascinated with that. Perhaps that is why I have learned so many languages and lived so many places (Afghanistan, Chad, Rwanda, Saudi Arabia). The fascination I had with Hoot Owl is still with me.

My favorite children’s picture book authors today tend to be the ones who write and illustrate. Peter Sis, Chris Van Allsberg, Allen Say, and Ed Young. They all write as well as they draw and all of them are a continual source of inspiration.

What are five highlights of your career thus far?

Two of them have to do with language. The first was when I translated one of my books (Seeker of Knowledge) into French and got it published, and the second was when I wrote a book in Brazilian Portuguese, which won several awards in Brazil.

The three other highlights would have to do with winning awards, I suppose. But when I think about it more, I think that they would have more to do with that special moment when someone comes up to me or writes and tells me how much my book has meant to him/her. This doesn’t always happen, but when it does, I realize that I have been lucky enough to meet the one person for whom I wrote a particular book. This is an odd concept, I suppose. One writes to communicate with the masses. I take a different view. I write to communicate with one, just one of the eight billion out there.

Do you have a favorite childhood food-related memory?

When I was a kid, one of my favorite dishes that my mother made was a Hungarian chicken dish: Paprakosh (her pronunciation), that she learned from her sister, who had married a Hungarian. It was simple: a fryer cut up, smothered in celery and paprika, baked in the oven with water until the chicken came off the bones. This she served over noodles.

My memories of that dish bring back others as well — about my mother and father and how supportive they were. My father was not a professional artist — an insurance salesman, but he had studied art — even went to the Chicago Art Institute until the Depression forced him to quit. (Here I will digress: one of the highlights of my career was to have my illustrations from Traveling Man on display at the Chicago Art Institute. My father would have been proud.)

My father taught me a lot, not just about drawing and painting, but about learning. We were always looking things up in the Britannica encyclopedias that we had. From him I learned to love learning, and this concept I try to infuse in my books. Yes, my books are often an intellectual stretch, but that is how one learns — by stretching and challenging one’s mind. My mother was always there encouraging me. This type of encouragement can never be underestimated.

Which authors or artists, living or dead, would you most like to have dinner with?

I would love to have dinner with Su Dong-Po, Horace, Hafiz, John Singer Sargent and Winslow Homer.

Finally, what are you working on now?

I have a collaborative book: Max and the Dumb Flower Picture (Charlesbridge); a cautionary tale I made up about anger: Tiger and Turtle (Roaring Brook Press); a story about building a school in Chad, Africa: Rain School (Houghton Mifflin), and a story about Gutenberg and how he produced the first printed book: From the Good Mountain (Roaring Brook Press).

Thanks so much for visiting and chatting with us today, Jim. We look forward to all your new books!

*

*Interior spreads from Silent Music posted by permission, copyright © 2008 James Rumford, published by Roaring Brook Press. All rights reserved.

*Interior spreads from Chee-lin posted by permission, copyright © 2008 James Rumford, published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. All rights reserved.

What a great interview. I quoteskimmed a bit of it for next Sunday’s post.

LikeLike

Great interview, Jama. James is a fascinating man!

Kelly Polark

LikeLike

Wonderful interview! It’s so great to learn about the person behind the name on the cover. (Just as with you! :D)

Do you think any of your Soup subjects would ever allow us to post questions for them here? I could think of several while reading Mr. Rumsford’s interview. 🙂

LikeLike

James Rumford

Thanks for introducing me to new author!

http://notsolongago.blogspot.com

LikeLike

I’m excited to see what words resonated with you the most!

LikeLike

Indeed he is. Thanks for stopping by to read, Kelly :)!

LikeLike

What were your questions?

LikeLike

Re: James Rumford

Hope you check out some of his books soon :)!

Welcome to alphabet soup; thanks for stopping in.

LikeLike

James Rumford

enjoyed it all!

LikeLike

*laughs* Well, one of them got answered by virtue of the fact that I re-read his interview just now and realized I had *mis*-read something he said. Oops.

I think I’d be curious to know which fiction books he considers “good” by his own definition (as stated above), or at least an example or two – and what about those books speaks to him.

It’s been a long day and I *know* there were some other questions which came to mind but right now I’m drawing a blank. Oh well. I commend his affection for languages; I love them, too, but not to the extent he does! I’m learning Chinese along with my elder daughter (age 6 – I attend her class so I know how to help with her homework) and, man, it’s tough. So I greatly admire that he has learned so many languages – and so many “nontraditional” ones (for most Americans) at that. Is he fluent in all of them?

LikeLike

Yes, I’m also curious about which fiction books he considers good :)! As for fluency, of course I don’t really know — I imagine differing degrees of fluency when there are so many languages involved. But still, isn’t it amazing? Especially the ability to decipher strange looking symbols, etc. Don’t you think he’d be a valuable asset to the CIA or something, able to decipher secret codes and stuff? Okay, I’m getting carried away . . .

LikeLike

Re: James Rumford

So glad. Thanks so much for reading!!

LikeLike

“A picture is not complete unless it is accompanied by words.”

Wow.

There’s a guy who takes his picture books seriously.

His art is GORGEOUS!!!!

LikeLike

Such beautiful work. “Picture books make it possible to explore the interactions between language and art.” Amen.

Jules

7-Imp

LikeLike

Very seriously. I don’t think I’ve ever heard anyone else say that. But the gift is, feeling this way, and then being able to execute that belief. I bemoan my lack of artistic talent every day.

LikeLike

It really is a fascinating dynamic :)!

LikeLike

What a cool guy!

And such a fascinating interview!

Thank you!

Becky

Wonders Never Cease

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it 🙂 . . .

LikeLike

James Rumford

Elaine M.

I had been so busy in the past week working on arrangements for our reading council dinner that was held last night that I thought I would never get around to reading your interview with James Rumford. And what a wonderful interview it is!

I heard James speak at Simmons College a few years ago. I think James Rumford is the loveliest man. He is so impassioned about his work. Everyhting he creates seems to come from his heart and the love of what he does–and his respect for all cultures. He creates the most marvelous books–for both children and adults.

Thanks, Jama, for giving us this in-depth look at one the finest authors and illustrators of picture books.

LikeLike

Re: James Rumford

Oh, I’m so glad you came back to read the interview, Elaine. You’re right — his passion definitely shines through in everything he does. We’re lucky to have someone so knowledgeable of languages and cultures creating these special books for children, and as you said, adults. I learn so much and can’t wait for more!

LikeLike

Love this interview. I went and read Silent Music after I saw the review on your blog. I loved it and learning the background of the author is always fun for me.

Cari @ Book Scoops

LikeLike

That’s awesome that you read and liked Silent Music. I learned a lot about Jim from interviewing him, and have even more appreciation for his work now.

LikeLike