The first time I heard Billie Holiday’s rendition of “Strange Fruit” I was confused. What was she . . . could she be . . . NO! . . . and then the awful realization that she was singing about lynching — one of the most horrific, unconscionable atrocities in American history.

Strangely enough, before I read Strange Fruit: Billie Holiday and the Power of a Protest Song by Gary Golio and Charlotte Riley-Webb, I hadn’t really thought of “Strange Fruit” as a protest song, at least not the kind of protest song popular at Labor Union rallies à la Woody Guthrie, or sung in unison at 60’s civil rights marches or counterculture anti-war sit-ins. Protest songs roused and inspired people to stand up to social injustice; they unified, mobilized and galvanized.

Of course “Strange Fruit” did all of these things, but I think it should be in a category of its own. It shocked and outraged people, leaving many anguished and ashamed. It was, and still is, hard to listen to, and it was hard on the singer, as it brought to bear her own struggles with racism, violence, drug and alcohol addiction — all the ugliness she had experienced as an African American woman. Billie’s performances of “Strange Fruit” could be thought of as visceral theater. Singing it became an act of courage, as she was sometimes “verbally or physically harassed” afterwards.

In this new picture book, we see how “Strange Fruit” became a masterwork of its genre with far-reaching implications, thanks to the combined efforts of three like-minded individuals — singer Billie Holiday, songwriter Abel Meeropol, and nightclub owner Barney Josephson.

Golio’s narrative begins when Billie is 23, an established singer with hit records and club appearances, who’d worked with “some of the finest jazz musicians in the country.” She was even singing with Artie Shaw, “as one of the first black singers to work in an all-white band.”

Though she was grateful for the opportunity, the racial discrimination she faced at New York City’s Blue Room proved to be too much. She wasn’t allowed to talk to the customers or walk around by herself in the hotel. She was confined in a small upstairs room before showtime and had to use the service elevator to get to the stage. When Artie wouldn’t stand up for her, Billie became furious and quit.

Billie had a very rough start in life — left with relatives as a baby, reform school at age 10 (for “a terrible thing done to her“), arrested and jailed at age 14. Billie’s love of music, especially jazz, kept her going through these difficult times. She decided early on that she wasn’t going to scrub floors like her mother. “She had a plan to be somebody.”

As a teenager she started singing in small clubs, developing her skills at improvisation, the “heart of jazz.” From small cafes to nightclubs, Billie gradually built a following. Her voice was distinctive, unforgettable, and she instinctively knew how to play with melody and lyrics in a way that transcended notes on a page. But the highs of her music were always tempered by feelings of anger, degradation and exclusion.

Laws separating whites and blacks made things tough for Billie wherever she went. In some places, she might have been killed for even standing next to a white person, onstage or off.

She dreamed of having a place to work where she could perform with anyone she wanted and everyone could listen to her sing.

Luckily, she got her wish when Barney Josephson, a former shoe salesman from New Jersey, opened the first integrated night club in the United States. Cafe Society in Greenwich Village not only featured black performers, but gave black customers the best seats in the house, unlike Harlem’s famous Cotton Club, which catered to white customers despite featuring the greatest black entertainers in the country.

Barney hired Billie to sing at Cafe Society, and in no time both she and the club were hugely successful. One day Abel Meeropol, a Jewish high school teacher/poet/songwriter from the Bronx who was “outraged by the ongoing racism and violence against American Negroes,” visited Barney to share a song he’d written. “Strange Fruit” had been inspired by a photo Abel had seen of a lynching. When Abel first sang it for Billie, she was unimpressed, but because Barney thought the song was important, Billie agreed to sing it as a favor to him.

She tried it out at a private party in Harlem. As she sang, she thought about her father, who had died after being turned away from an all-white hospital. After her final note, there was stunned silence. This reaction convinced Billie she must indeed sing Abel’s song.

“Strange Fruit” made its public debut at Cafe Society in 1939 under Barney’s careful direction. It would be the last song in Billie’s set, with no encores. The room was darkened except for a lone spotlight on Billie’s face. After Billie’s gut-wrenching performance, the spotlight went off, she left the stage, and then there was nothing but silence . . . followed by a standing ovation and applause.

“Strange Fruit” made Billie Holiday a star. People flocked to Cafe Society especially to hear her sing it. Her recording of “Strange Fruit” sold a million copies even though most radio stations refused to play it.

Though performing the song sometimes sickened her, Billie continued to sing it as a form of personal protest. It was a way of voicing the suffering of her people. It was a way of telling everyone in the audience, ‘I may be here for your entertainment, but I’m also here so that you will never forget this particular horror.’

Golio’s compelling, age appropriate account of “Strange Fruit’s” genesis and significance is void of sensationalism or melodrama. He doesn’t mention that Billie was raped, or that she and her mother were jailed for prostitution, yet he was able to convey how hardship, poverty and trauma steeled Billie’s determination, giving her the strength to indeed “be somebody.”

We’re able to see how Billie tapped into personal pain and sadness until she came to embody the song in a way that no one else has been able to replicate.

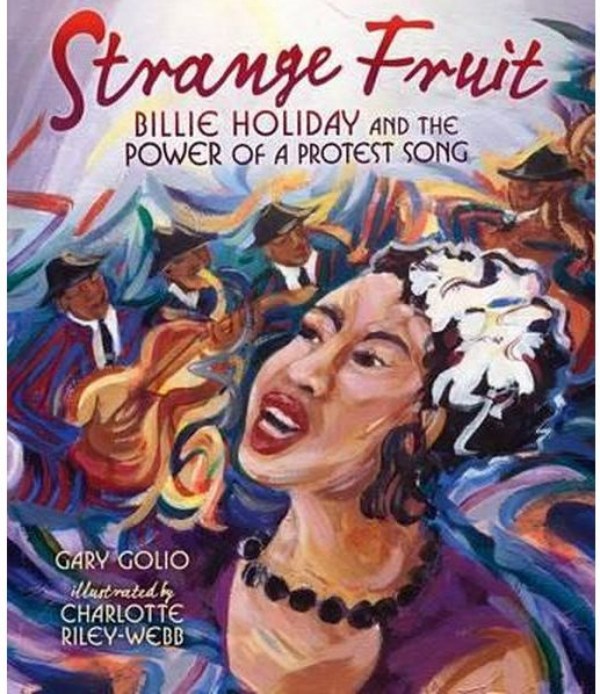

Charlotte Riley-Webb’s evocative acrylic paint and tissue paper illustrations are music and emotion personified. Bold, sweeping strokes of deep, rich colors embody passion, tumult, excitement, pain, and exaltation. Whorls and flame-like swirls suggest the constant movement of improvisation; jazz is a free-flowing form that won’t be contained.

There is scintillating glamor and city lights, a sensation of cacophony, a feeling of being enveloped in soaring notes, wandering melodies, dynamic rhythms, sassy syncopation. Lyrics from the song appear to be painted in blood — “the blood on the leaves and blood at the root.” In the spread of a young Billie in crisis mode, her arms are braced against her chest in defense, desperation, and defiance, as multiple hands grab at her. The fury and panic are palpable in this powerful representation of Billie being traumatized.

Billie’s struggles are handled with balance and sensitivity. The book is a timely must-read that is best shared in a setting where a parent or teacher can guide discussion, answer questions, and suggest resources for further study. Back matter includes more details about the song, lynching, and Billie’s short life.

Billie Holiday is someone all young readers should know, as she was someone who was able to effectively utilize her craft for a cause. More than a signature song, more than a protest song, “Strange Fruit” shows how art can be a powerful, non-violent agent of change.

Because of three people, all of whom sought to fight racism — one who had lived the pain of discrimination, one who was able to put this pain into words and music, and a third who provided a venue to spread the message, we have this masterful “song of the century,” a “historical document” that became a cornerstone of the civil rights movement. This story will likely inspire readers to pursue their passions in ways to help make a more just, tolerant society.

Here’s a live recording of Billie performing “Strange Fruit” in London (1959). It may well be one of the last times she ever performed it, as she died the same year. Though not mentioned in the book, “Strange Fruit” was initially written as a poem called “Bitter Fruit” before Meeropol set it to music.

*

STRANGE FRUIT

Southern trees bear a strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black body swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the popular trees.

Pastoral scene of the gallant South,

The bulging eyes and the twisted mouth,

Scent of magnolia, sweet and fresh,

And the sudden smell of burning flesh!

Here is a fruit for the crows to pluck,

For the rain to gather, for the wind to suck,

For the sun to rot, for a tree to drop,

Here is a strange and bitter crop.

*

STRANGE FRUIT: Billie Holiday and the Power of a Protest Song

written by Gary Golio

illustrated by Charlotte Riley-Webb

published by Millbrook Press, February 2017

Picture Book Biography for ages 8+, 40 pp.

*Includes Author’s Notes, Source Notes and Bibliography

**Starred Reviews** from Kirkus and Publishers Weekly

♥ Interview with illustrator Charlotte Riley-Webb and Julie Danielson at Kirkus

♥ Gary Golio and Charlotte Riley-Webb interview each other at Elizabeth Dulemba’s blog

♥ Detailed Teaching Guide at Six Trait Gurus

*

The witty and talented Diane Mayr is hosting the Roundup at Random Noodling (still one of my favorite blog names ever). Tango over there to check out the full menu of poetic goodness being shared in the blogosphere this week. Have a wonderful holiday weekend!

The witty and talented Diane Mayr is hosting the Roundup at Random Noodling (still one of my favorite blog names ever). Tango over there to check out the full menu of poetic goodness being shared in the blogosphere this week. Have a wonderful holiday weekend!

*Interior spreads posted by permission of the publisher, text copyright © 2017 Gary Golio, illustrations © 2017 Charlotte Riley-Webb, published by Millbrook Press. All rights reserved.

Copyright © 2017 Jama Rattigan of Jama’s Alphabet Soup. All rights reserved.

Powerful post, Jama. We must not ever forget our past. We have to own it to not revisit it. An important book in today’s world where fear is the dominant note in the political dialogue.

LikeLike

Very true, Brenda. Fear is definitely a big factor. Willful ignorance is another.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And anger. Resentment. Jealousy.

LikeLike

I have mixed feelings about picture book treatments of mature issues. One never knows where to put them in a public library! (Picture book section? Juvenile nonfiction? Teacher materials section? Young adult?) And there’s always the fear that a child not ready to deal with the issues emotionally will pick up the book and not have the discussions necessary to make the issue understood. The pictures draw them in… Yes, that’s where parents and teachers should enter the picture, but, we all know that parents/teachers are not always aware of what their kids are reading/doing.

Thanks for giving me something to think about. I’m not an advocate of censorship, just in making connections between books and their readers.

LikeLike

We have a section in our libraries for picture books for older readers that’s separate from the nonfiction and regular picture books sections, but still in the children’s area. We don’t limit access to it, of course, but it does often make it easier for caregivers and and educators find picture books for use in schools, or with older kids.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I totally understand why you have mixed feelings. It’s quite a dilemma when you weigh the options: shelve the book according to your best judgment and hope proper guidance is available for the reader, or not offer the book at all. Difficult/controversial subjects are hard to write about in the first place, yet they are needed as they do lead to valuable conversations and further study, and hopefully more understanding and compassion.

LikeLike

Jama, you have given me another reason to adore Billie Holiday. I have always admired her music, and now I am absolutely moved by her story. Thanks for sharing this amazing book!

LikeLike

I enjoyed this book as I didn’t know all the facts behind her connection with “Strange Fruit.” Was surprised to discover it was first written as a poem!

LikeLike

Wow. What a powerful story. Thank you for sharing it with such feeling and insight.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed the post. Gary and Charlotte have done a marvelous job with a difficult and painful subject.

LikeLike

Thank you, Jama, for this important post. We adore her music, but didn’t know the background to “Strange Fruit.”

LikeLike

I didn’t know all the background either. I learn so many surprising things from children’s books.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I can understand Diane’s conundrum.

Did you hear about the British singer who said she would sing at 45’s inauguration if she could sing “Strange Fruit”? (Didn’t happen)

LikeLike

Yes, I did hear that story. Kudos to her for standing her ground.

LikeLike

Many biographies are being published recently of those who should be honored, and Diane is right, some are for mature children, and need a conversation with an adult. This book is on my list, but the library has a lot of holds! Thanks for sharing your opinions about it, Jama, that it is for older readers. I love Billie Holiday’s voice, a person who persisted in her art despite the walls she had to climb.

LikeLike

Her voice was very distinctive — it’s like you can hear her personal stories in every song.

LikeLike

Oh I love Billie Holiday. Can’t wait to see this book!

LikeLike

Enjoy it!

LikeLike

Thank you for bringing this interesting and powerful story to your audience. Hopefully the book does very well.

LikeLike

I do hope it is widely used in the classroom. With teachers’ guidance seems to be the best way to introduce Billie and the song, and of course it ties in nicely with history, culture, music studies, etc.

LikeLike

It’s on my list to buy. I love the work of Gary Folio. Thank you for this powerful review.

LikeLike

Glad to hear you plan to purchase it, Jone!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have this on our library suggest a title program. That art work is absolutely stunning. Can’t wait to read it!!

LikeLike

Yay!! You are so conscientious about requesting titles — I try to do the same whenever possible. 🙂

LikeLike

Wow–this looks like a powerful read.

My book club discussed Colson Whitehead’s Underground Railroad this week. Talk about a difficult and important book–we discussed the importance of bearing witness and remembering. I would think this book could do the same for kids. I could see it stimulating terrific discussions for middle school and high school kids (and maybe mature upper elementary.) I hope it reaches those audiences.

LikeLike

Yes, this book is the perfect way to engender meaningful discussions about racial prejudice — sadly, a topic that’s especially relevant today in light of what’s going on.

LikeLike

Thanks for this in-depth look at a very powerful and sad story of all of our history. I hope it’s seen and read by many, I will definitely bring it up in conversation. The art is rich and deep also.

LikeLike

Thanks for reading, Michelle. We can only hope that books like these help young people understand the painful parts of our history and why it’s so important not to repeat them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh my. Those lyrics and Billie Holiday’s rendition gave me shivers. Thanks for sharing about this important book.

LikeLike

The ongoing impact and relevance of this one song is amazing.

LikeLike

It is beyond comprehension what humans can do, sometimes. We must always keep a soft heart and compassion – and see the heart that beats in all of us. A moving post, Jama. And yes – so true what Diane has said about the importance of readiness and discussion with a book like this.

LikeLike

You’re right — readiness and discussion are key, and I have confidence in our many, many great teachers, librarians and parents to educate and address young people’s concerns about issues like these.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this important poem and the story of how it became an iconic song for Billie Holliday.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re very welcome. Thanks for reading, Mary Lee!

LikeLike

Thanks SO much for this post, Jama. Additional thanks Gary, Charlotte and Carol Hinz at Lerner for bringing this book into the world. Kids need to know about this story.

LikeLike

Hi Charles! I agree that kids should know about this story. It’s inspiring to learn how one song can make such a difference. BH had a hard life, but there were moments of great joy too. I’m grateful her singular talent was recognized in her lifetime.

LikeLike

Jama, you did an outstanding job of providing plenty of information for the reader to enlarge our perspective of Billie Holiday. I have been a fan of hers for a long time. Many facts you shared were unknown to me.

LikeLike

Good to know you’re a BH fan, Carol. I learned some new things by reading this book too.

LikeLike

As others mentioned, I learned a lot here about the background of Strange Fruit. Thanks, Jama. You always enlighten and inform. What an astounding book.

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed learning the backstory of this song. I had no idea either and found it fascinating.

LikeLike