“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

So begins one of the greatest fantasies ever written. The Hobbit, by J.R.R. Tolkien, is deliciousness in itself, and this prelude to Tolkien’s masterwork trilogy, Lord of the Rings, begins with a tea party!

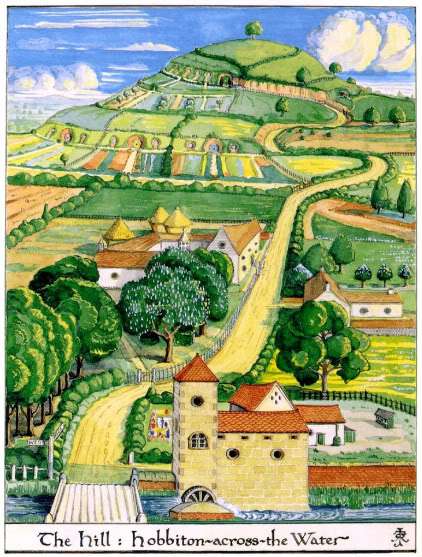

In Chapter One, “The Unexpected Party,” we are introduced to the diminutive Bilbo Baggins. In the bucolic world of Middle-earth, an entire race of people under four feet tall practice farming, eat at least six meals a day, never have to wear shoes, and prize socializing and comfort above all.

Bilbo is middle-aged and fairly well-to-do, and when the story begins, he is perfectly happy with his life just the way it is. He has two breakfasts, elevenses, lunch, afternoon tea, supper and an after-supper snack — and several pantries in the cellar full of provisions. The first time I read this story back in high school, I immediately wanted to live in The Hill with Bilbo and his friends. They lived their lives with a certain gentle nobility and simple joy. I could identify with their shyness of the Big People, and found their charm irresistible.

“By some curious chance one morning long ago in the quiet of the world, when there was far less noise and more green,” Bilbo was standing at his round, green front door smoking a pipe after breakfast when Gandalf the Wizard comes by. He was taken with Gandalf because of his reputation for wonderful tales of goblins and wizards and dragons, and for making excellent fireworks. But he politely declines when Gandalf mentions he is seeking someone for an excellent adventure. Before hurrying back inside, he invites Gandalf to tea the following day, regretting it as soon as he shuts the door.

Relieved that he has avoided an unwanted adventure, Bilbo is flummoxed the next day when he is visited by not one or two, but a throng of dwarves — 13 to be exact, who act like they had been expected all along. Bilbo, the good host, invites them to tea, for “what would you do, if an uninvited dwarf came and hung his things up in your hall without a word of explanation?”

Gandalf finally arrives, and all this unexpected company keeps Bilbo hopping. Not only are they devouring all the seed-cakes he had baked especially for his after supper snack, but they keep asking for everything under the sun, except tea:

Some called for ale, and some for porter, and one for coffee, and all of them for cakes . . . A big jug of coffee had just been set in the hearth, the seed-cakes were gone, and the dwarves were starting on a round of buttered scones . . .

After the great Thorin Oakenshield arrives (a very important dwarf), he and Gandalf ask for red wine (no tea, thank you)! And the others, who haven’t stopped eating since they arrived, chime in:

‘And raspberry jam and apple-tart,’ said Bifur.

‘And mince-pies and cheese,’ said Bofur.

‘And pork-pie and salad,’ said Bombur.

‘And more cakes — and ale — and coffee, if you don’t mind,’ called the other dwarves through the door.

‘Put on a few eggs, there’s a good fellow!’ Gandalf called after him, as the hobbit stumped off to the pantries. ‘And just bring out the cold chicken and pickles!’

Feeling more and more put out, Bilbo feels obligated to invite them to supper, and they end up staying overnight (and ordering big breakfasts before retiring). After supper, the dwarves play beautiful music and sing about reclaiming the Lonely Mountain and its treasure, guarded by the dragon, Smaug:

Far over the misty mountains grim

To dungeons deep and caverns dim

We must away, ere break of day,

To win our harps and gold from him!

As they sang the hobbit felt the love of beautiful things made by hands and by cunning and by magic moving through him, a fierce and jealous love, the desire of the hearts of dwarves. Then something Tookish woke up inside him, and he wished to go and see the great mountains, and hear the pine-trees and the waterfalls, and explore the caves, and wear a sword instead of a walking-stick.

And so a somewhat reluctant, home-loving hobbit sets out on a grand adventure, which all began when unexpected guests arrived for tea.

Since one never knows when an opportunity like this will present itself, it is always best to have some seed-cakes on hand. This is an authentic recipe from 16-17th century England adapted for the modern kitchen. This type of sweet, almost bread-like round cake was very common during the Middle Ages, and is also described in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales.

I think your dwarves will like it!

SEED CAKE

1-1/2 cups unbleached flour

1 cup cracked wheat flour

1 pkg. yeast

1/8 cup warm ale

1/8 tsp salt

4 oz (1 stick) sweet butter

3/4 cup sugar

2 eggs, beaten

1 T seed (crushed anise, caraway, coriander, cardamon, etc.)

1/2 – 1 cup milk

Sift together the flours and salt; set aside in large bowl. Dissolve yeast in warm ale, along with 1/8 tsp of the flour mixture. Cream together the butter and sugar. Beat in eggs and seeds. Make a well in the flour and add the dissolved yeast. Fold flour into yeast mixture, then fold in the butter. Slowly beat in enough milk to make a smooth, thick batter. Pour batter in an 8″ round greased cake pan. Bake in middle of oven at 350 degrees for 45 minutes, or until a toothpick inserted in the center comes out clean. Let cool slightly before turning onto a cake rack.

*