My grandmother and I had a unique way of communicating. Our made-up language was a hodgepodge of Korean, Hawaiian Creole English (Pidgin), broken English and American slang. We stuck to simple subjects as we watched our favorite soaps or gossiped about other family members.

While in middle school, I sometimes greeted her with a simple “Ohayō” or “Kon’nichiwa,” and she would shush me, her face like thunder. Since many of my classmates were Japanese, I naturally echoed some of what they said. My mom finally explained why Grandma got upset: from 1910 to 1945 the Japanese had occupied her homeland; Koreans were assigned Japanese names and the Korean language had been banned.

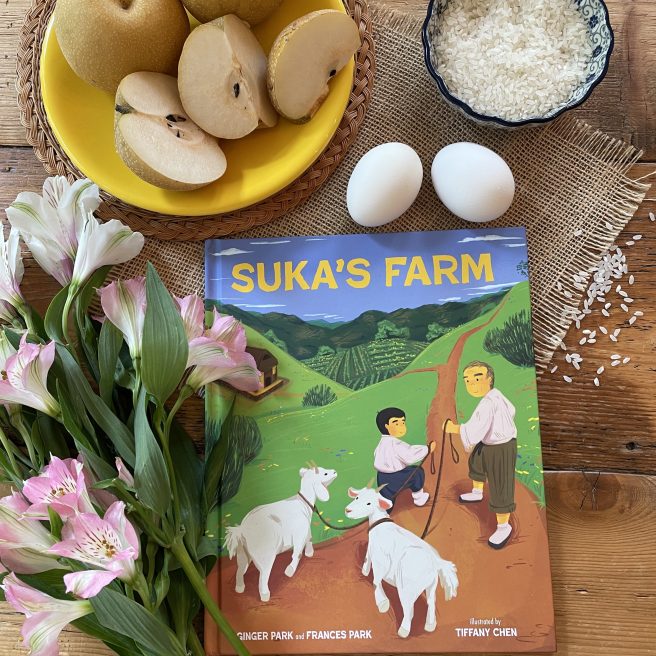

I thought of her while reading Suka’s Farm (Albert Whitman, 2025), a new picture book by Ginger Park and Frances Park, set in 1941 Korea. Illustrated by Tiffany Chen, this touching story of an unlikely friendship between an elderly Japanese farmer and a hungry Korean boy warms the heart and offers a much-needed glimmer of hope for humanity.

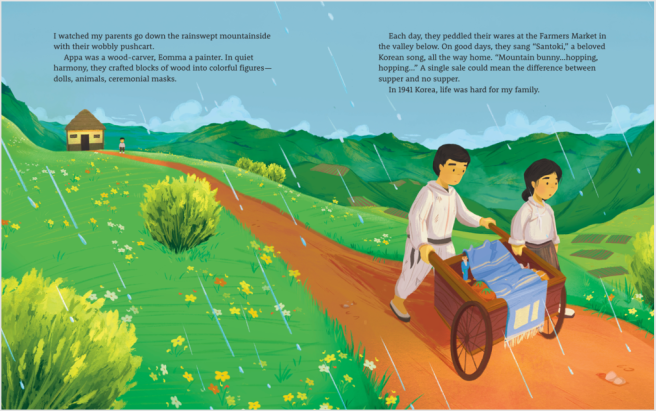

As the story opens, we learn Kwan lives on a quiet mountainside with his artisan parents, who eke out a living by selling their woodcarvings at the Farmers Market. Times are hard as they struggle to get by with meager bowls of rice porridge for supper. One night, Kwan overhears his worried parents say they only have a handful of rice left.

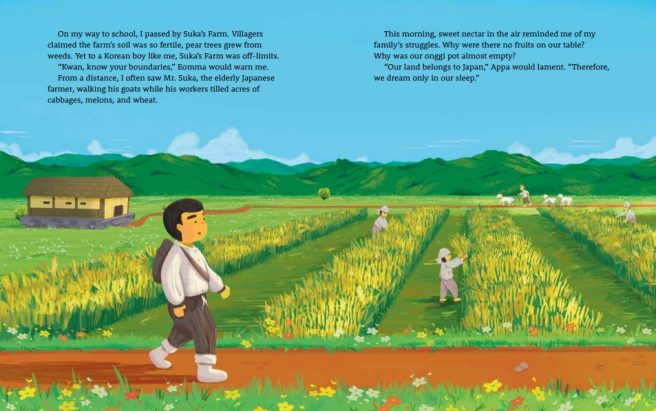

When Kwan passes Suka’s Farm on his way to school the next morning, he’s reminded of his family’s struggles. He sees pear trees growing from fertile soil, and acres of cabbages, melons and wheat — yet none of these foods ever appear on Kwan’s table. That’s because the land belongs to Japan, and Suka’s Farm is off-limits to Korean boys like him.

Still, Kwan is determined to help his family and, “as if in a dream without boundaries,” he steps onto the farm and musters up the courage to ask gruff Mr. Suka for a job. Kwan respectfully introduces himself as Aoki, the Japanese name he’d been assigned by law.

Mr. Suka is dismissive and rejects Kwan’s offer of work. How could a child help him? Kwan explains he could help with the goats, begging Mr. Suka because his family is hungry. Mr. Suka tells Kwan to go to school, but just as the boy is leaving the barn, he calls him back. He agrees to let Kwan work on a trial basis.

So, the next day, Kwan arrives before dawn, bearing a gift for Mr. Suka from his parents — a carved wooden goat. Though puzzled by the gift, he thanks Kwan, then introduces him to his little herd of goats, each of which has a name. Kwan and the goats, whom Mr. Suka loves like family, become fast friends.

Continue reading